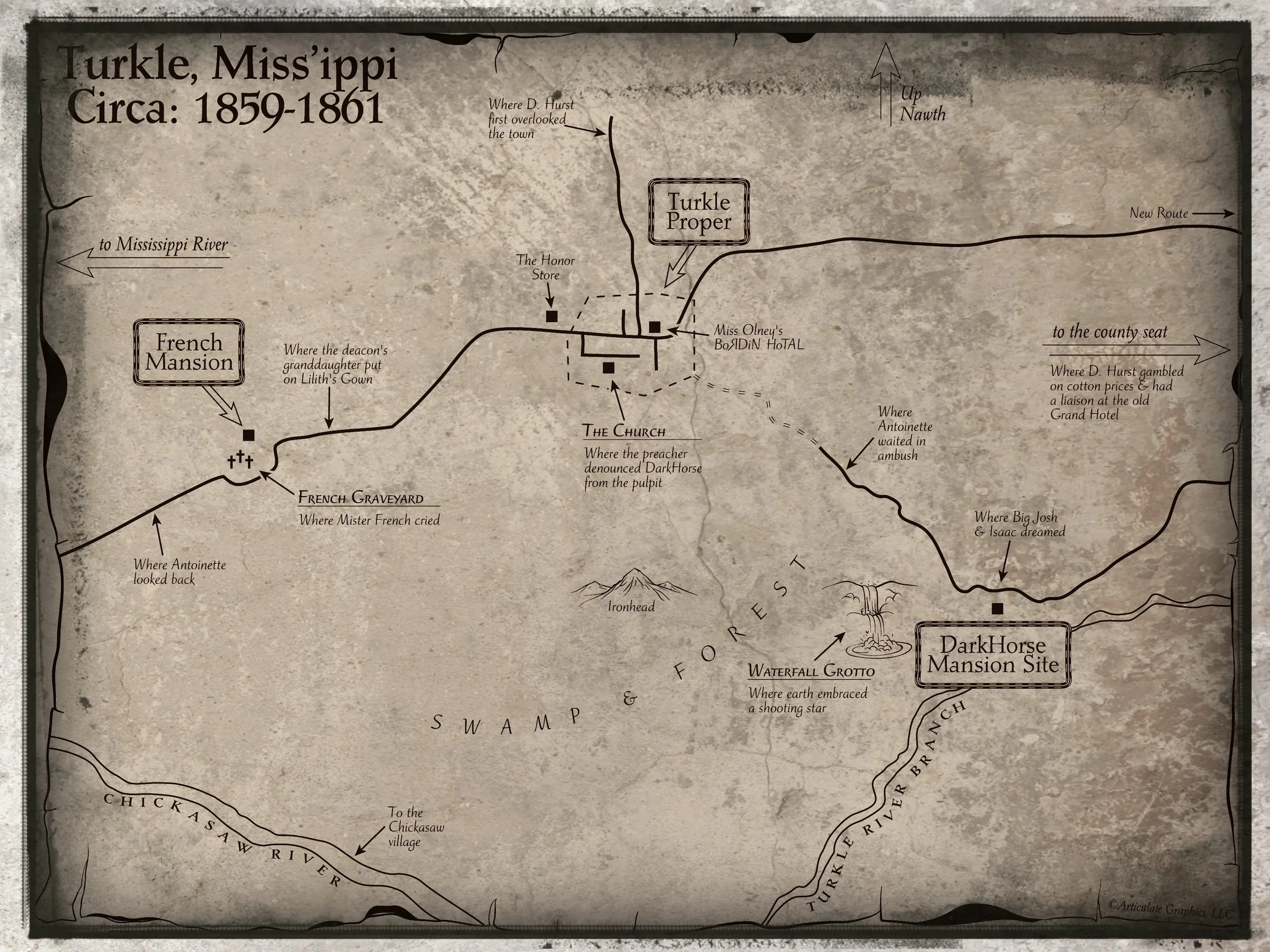

Black History Month; Good Time to Research The Lies That Bind Sequel

Right now, I’m working on Honor Among Outcasts, Book 2 of my DarkHorse Trilogy and the sequel to Book 1, The Lies That Bind. I'm not just working on developing the story, but preparing the research, too. Black History Month couldn’t come at a better time to stimulate my thoughts and feelings, and to offer fresh insights into the Black Experience in America, which has been nothing short of epic on the world stage.

The new novel will take place in Missouri—gasp!—to where the DarkHorse partners have fled from Mississippi. Beginning in 1863, Durk, Big Josh, Isaac, and the other former slaves will finally get their chance to put on the Union uniform, to fight for the liberation of all Southern slaves.

But things are not as simple as they anticipate.

Of course, visionary charlatan Durk Hurst, continuing his role from The Lies That Bind as the “white front man” for the DarkHorse partnership, has worked alongside the others all along, sharing their joys and their hardships.

In the new book, Durk gets the group through these rough times by characterizing his partners as “contraband” laborers, supposedly “liberated” by himself. Sometimes he calls them his own “manumission-freed former slaves,” depending on what story he is spinning and to whom on any given day, to serve whatever ends Durk’s instincts dictate. Of course, sometimes Hurst’s golden tongue does get them out of trouble—and sometimes it gets them deeper into trouble. Oh, well. Durk may be part-Seminole, but he’s the only white face his partners have to depend on.

Brutal, War-Torn Missouri

Prior to 1863, when the story begins, General Samuel Curtis had defeated the Confederate army at Pea Ridge, and chased it to Arkansas. Was that the end of fighting in Missouri? No, the worst was just beginning. During the war, Missouri had more battles and clashes than any other state besides Virginia. But they weren’t set-piece battles.

After Pea Ridge, Missouri became neighbor against neighbor, terrible stuff. The state quickly devolved into hit-and-run guerrilla attacks: civilians were victims of atrocities, and generally, few prisoners from either side lived to tell the tale. Civil war is the nastiest kind, and guerrilla war the worst of all. Look at Syria today. Civil war, guerrillas, atrocities, refugees, devastation. Well, Missouri had all that—and more!

Bushwhacker Brutality

Missouri’s pro-slavery guerrillas, called “bushwhackers”—yes, you’ve heard that reviled term—raided Lawrence, Kansas, and killed hundreds of civilians before returning home. In desperation, the Union military authority issued Order No. 11, which emptied out more than three counties in western Missouri, where many guerrillas lived. I mean cleaned them out, including pro-Union civilians, everybody. Women with husbands at war and children to raise, widows, the elderly. Many destitute, without means to carry a few goods to sustain them, were forced onto the road. And it wasn’t done in a kindly way, as you might well guess. Union soldiers, like their bushwhacker counterparts, robbed and burned. That was Missouri.

The African-American War Effort

Since twelve of the thirteen DarkHorse partners are black, naturally I’m busy researching and learning about that experience during the war. Two books I’m excited to have found are A Grand Army of Black Men, edited by Edwin S. Redkey (Cambridge University Press); and African American Faces of the Civil War: An Album, by Ronald S. Coddington (The Johns Hopkins University Press/Baltimore). See Library of Congress webcast discussion of the Coddington book.

I’m also very happy to be studying Guerrillas in Civil War Missouri, by James W. Erwin (The History Press); and A Rough Business: Fighting the Civil War in Missouri, edited by William Garrett Piston (The State Historical Society of Missouri).

Real history must never be forgotten, least we repeat our errors. And as I delve more deeply into our country’s history, the clearer it becomes that history itself is truly stranger than fiction.

Enjoy reading The Lies That Bind, and I’ll keep working on Honor Among Outcasts.

Coming up:

Book Launch for The Lies That Bind, Feb. 18, University of Missouri-St. Louis

LA Talk Radio's “The Writer's Block”

Check out my online interviews:

Hangin With,” G.W. Pomichter’s video show (30 min.)

David Clarke’s “Different Strokes for Different Folks” (58 min.)